by Lawrence Brock and Laurence Haughton

Does curiosity matter?

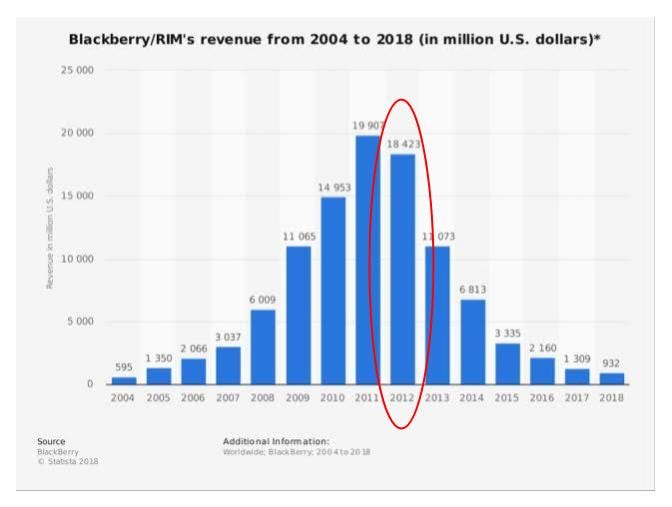

Consider Canadian multinational Blackberry, who almost doubled their sales revenue every year between 2003 and 2011.

So what happened in 2012? It wasn’t the arrival of Apple’s iPhone. That was released in 2007.

In 2012 Blackberry’s lack of curiosity caught up with them. Founder, Mike Lazaridis famously said, “Try typing a webkey on a touchscreen on an Apple iPhone, that’s a real challenge.” (Steve Jobs didn’t care. “Your thumbs will get smarter,” he said) Blackberry were overconfident, due to their history of success, that they had no curiosity about the iPhone. Within a few years they were a niche player and today they no longer make phones.

Blackberry isn’t alone — only 60 companies that appeared in the Fortune 500 in 1955 exist today. The average lifespan of a top US corporation has halved over the last 30 years.

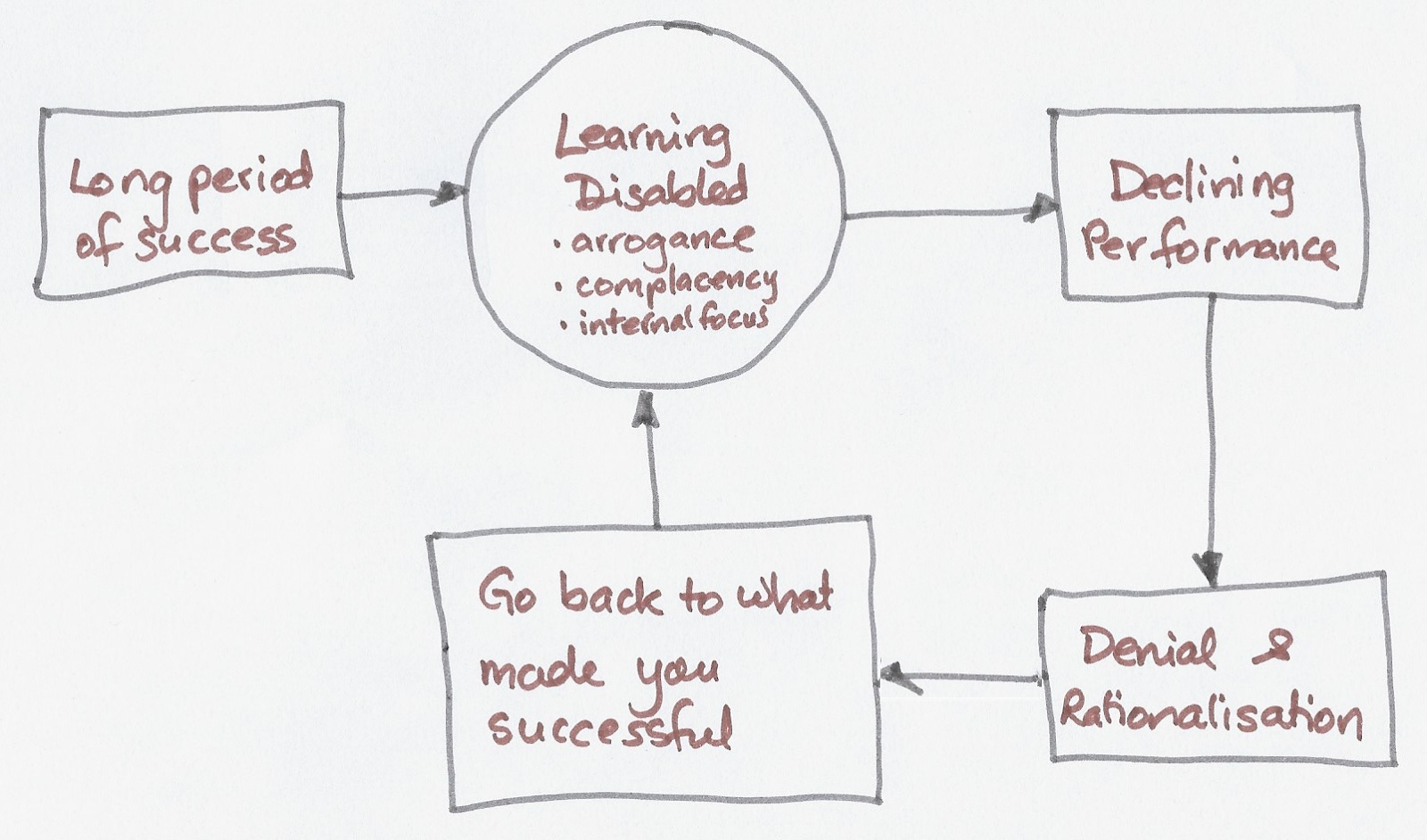

Success can turn into a death spiral if you stop asking questions and insist you already know the answers.

There’s a fascinating study, in “Why Leaders Don’t Learn from Success”, where students worked on two decision-making problems. After submitting their solutions to the first problem, the participants were told whether they had succeeded. They were then given time to reflect before starting the second problem. Compared with the people who failed at the first problem, those who had succeeded spent significantly less time reflecting on the strategies they’d used: Those who succeeded on the first task were more likely to fail on the second. They had stopped being curious.

Survival depends on an organisation’s ability to be customer obsessed, strategically aligned, quick and adaptable, purpose-driven and highly collaborative. The skill common to all these attributes is curiosity.

Everybody on a team (not just the C suite) needs to be noticing and understanding the sometimes subtle changes in their ecosystem. Curiosity is fundamental to an enquiring mindset.

How do you encourage your staff to be more curious?

There are different kinds of curiosity:

Perceptual — noticing something has changed e.g. “Can I smell smoke?”

Epistemic — directing our interest toward learning e.g. “What could I do to be better?”

Diversive — deciding to shift our attention e.g. “What is happening over there?”

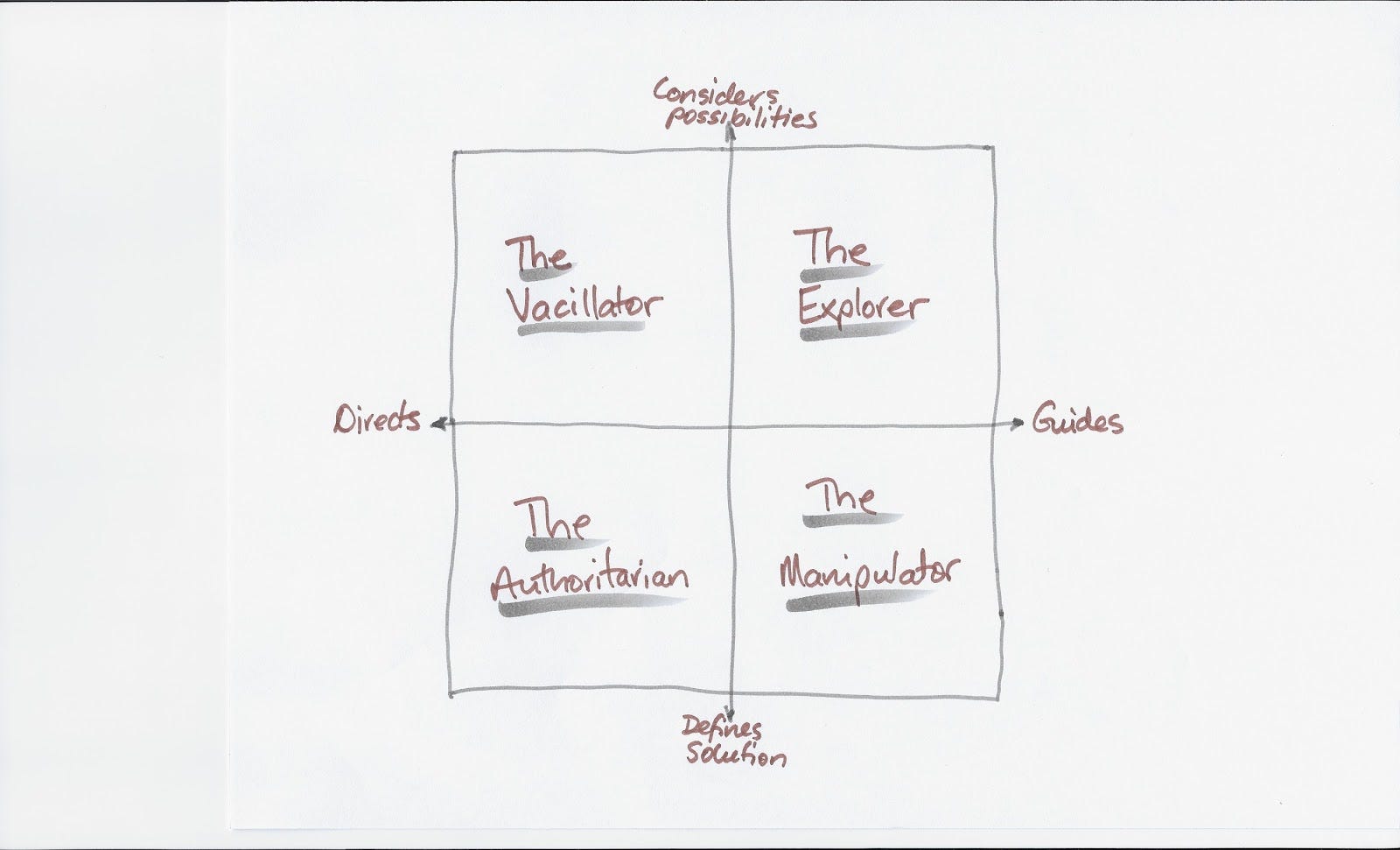

Encourage your team to remain open to new or unexpected possibilities, and guide rather than direct their reports. If they move too quickly to solution mode or dictate how people should work, your managers will stifle curious behaviour. Consider where each member of your management team fits within the curiosity matrix:

The Authority

Is most comfortable being the source of knowledge and providing constant, clear instructions. This manager places a high value on knowing the correct answer and is quick to apportion blame when there is failure. The solution is always clear from the outset to The Authority and the team will remain disengaged.

The Vacillator

Believes in the divine efficiency of hierarchy but accepts the world is ambiguous. The Vacillator wants to appear decisive but changes their mind based on the latest information. Often found with a perfectionist streak, this manager values decisiveness and at the same time, tries to stay open to new possibilities. The result is a very busy manager and a team bouncing off the walls.

The Manipulator

The manager who delegates to their team but retains an iron-grip on the shape of the solution, resulting in their team feeling deceived. The tighter the manager holds on to their detailed vision of success, while also encouraging their team to explore new ideas, the greater the sense of frustration when they find those ideas blocked.

The Explorer

A manager who encourages their team to try different approaches and provides support as needed to ensure their success. This can feel risky but is actually the safest quadrant.

Here are four practical ways to encourage your team’s curiosity skills.

Bake curiosity into your processes

Review all processes and add a questioning stage if one is missing. Ensure all future processes include at least one type of inquiry step, such as identifying risks or information gaps. Project or initiative reviews are another important way to check that the right questions are being asked. Rewrite meeting agendas into a series of questions. Celebrate curiosity — people will remain curious if it is safe to be so.

Reward curious behaviour

Recognise people who ask good questions. Reinforce the importance of taking an open, non-judgmental, inquiring position by rewarding good examples with public recognition. Protect individuals who ask questions as they try to understand. There may be others who don’t want to wait and who shut down the line of inquiry since they believe momentum is more important. Remind them there is no such thing as a dumb question.

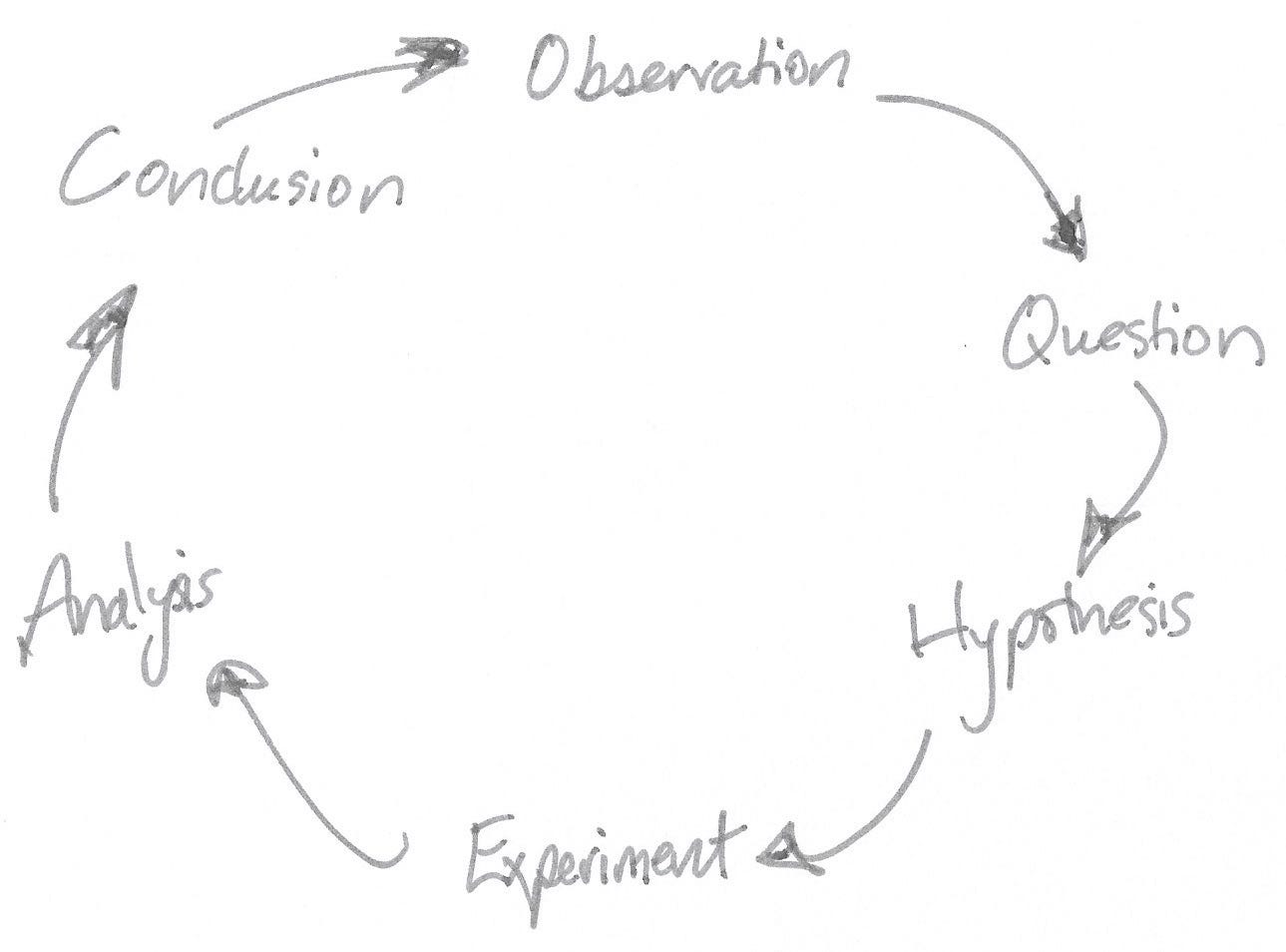

Use the scientific method

Since the Middle Ages, the cycle of hypothesis, prediction, testing and questioning has been the gold standard for accelerated learning. How you do this will depend on your organisational culture, however it is important to remember that humility is the foundation quality of the scientific method. “Inquiry regards itself as fallible.”

Summary

Inspire your people to keep an open mind. Expose them to different viewpoints and sources of creativity. Challenge them to argue from an opposing view. Be alert to topics or tasks the team finds boring and show them how an inquiring mindset makes everything more interesting.

As you encourage their questioning, watch your own speech — for example your selection of adjectives. Describing someone’s actions as “impulsive” is quite different to saying they are “instinctive”. Words carry judgements whether we mean them to or not. And when the boss speaks, everybody is quick to read between the lines.

Show the importance of identifying assumptions — especially when they are accepted as ‘common knowledge’, ‘best practice’, or ‘the wisdom of experience’. There is nothing inherently wrong with assumptions (they might be correct) but they remain risks until validated.

Get your people comfortable with asking questions. Help them understand that questions are more powerful than statements demonstrating capability.

Here’s a method you can teach your team, the ‘Count to Three’ rule of conversations:

- There are points in a conversation where you can add your own experiences or opinions. Your colleague might say “I could never move to the provinces, I’m a big city person”, and you can immediately think of close friends who moved to a regional town and loved it. But instead, you count ‘one’, and ask “What is it about city living you’d miss most if you moved to a smaller town?”

- Your colleague says, “It took me much longer than I expected to find a new job…” While you could sympathise by recounting your own stories of job seeking, you count ‘two’ instead, and ask “Which recruitment companies do you think did the best job?”

- Your colleague says “My favourite movie last year was The Florida Project”. Instead of telling them Willem Dafoe is one of your favourite actors, you count “three” and ask, “What did you think of the ending?”

Only after substituting three questions for comments, do you allow yourself the option to contribute an opinion.