by Lawrence Brock and Laurence Haughton

Decision making is risky. Go too slow and you risk the nearly irreversible costs of delay like missing a big opportunity (see how Apple squandered a 3 year lead with Siri) or looking timid, hesitant and very unleader-like. Go too fast and you risk the cost of wasting time and money by getting it wrong (see Waikato District Health Board finally admits defeat with their SmartHealth venture) or looking impulsive and unreliable (also very unleader-like).

There are good arguments for not moving too fast. Books such as Wait suggest that putting off decisions to the last possible moment, gives us more time to gather and analyse information, and create strategy. In our experience waiting sometimes allows problems to solve themselves. “Don’t just do something… sit there,” has been great advice.

On the other hand, there is a lot to be said for deciding fast. It’s the most powerful prescription for neutralising organisational resistance to change (kaizen blitzkrieg), it’s an awesome competitive advantage (grow fast or die slow) and when you can tell everyone “We blow through speed-bumps” you become irresistibly attractive internally and externally.

So how do you choose? When is it better to go slow, or fast?

Here are four tools for different decision making situations that help:

1. Every decision is a door

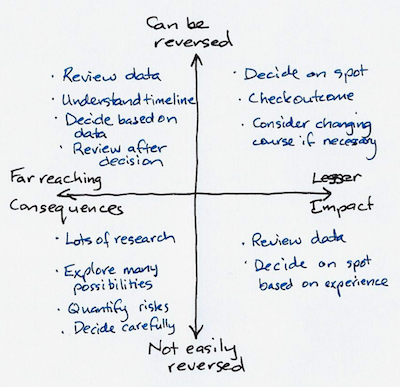

This is first because it’s simplest. Jeff Bezos (annual letter to shareholders) imagines each decision is a door.

Door 1: This door locks after you pass through — you can’t reverse the decision if you discover you don’t like what’s on the other side. These decisions should be made methodically, with great deliberation and consultation. They take longer and involve more people.

Door 2: A two-way door lets you back in if you don’t like the consequences. Because you can change your mind, these decisions can be made faster and usually involve fewer people.

However, Bezos argues strongly against ‘one-size fits all’ decision making which he thinks is a significant and all too common brake on organisational speed and inventiveness. This is a good reminder to become comfortable with several models for structuring your decision making.

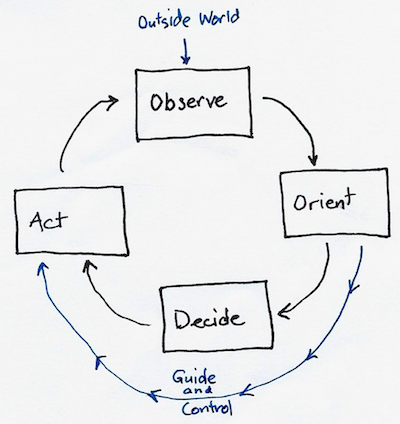

2. OODA

The Observe — Orient — Decide — Act loop is a decision cycle developed by military strategist John Boyd to improve competitive advantage by deciding faster than your opponent. Boyd used OODA as a combat instructor to take his F-86 fighter from complete disadvantage to complete advantage in forty seconds!

While his model has military origins, it would be a mistake to assume it relies on command and control. (Boyd rebelled against the slow-moving brass again and again.) Modern military doctrine favours bottom-up decision trusting commanders on the scene will appreciate local conditions best, and are competent to make independent decisions consistent with their commander’s intentions.

Note the ‘guide and control’ sub-loop which has echoes of Management by Objectives’ requirement for ‘monitoring and supporting’ teams. The OODA loop method is great for moving fast but be careful not to leave people behind or expect blind obedience.

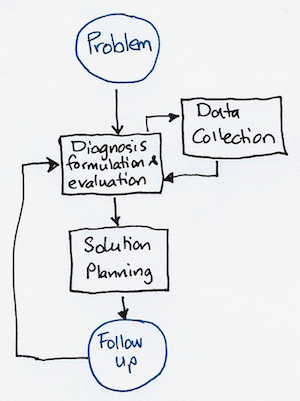

3. Hypothesis Driven

This is similar to diagnostic decision making used in the health sector. You are presented with a problem or opportunity and start looking for data to diagnose what might be happening. Once you have an evidence-based hypothesis you can begin to consider the most appropriate treatment.

I find this model excellent for dealing with one-to-one situations such as individual coaching or HR issues such as someone getting negative feedback from the rest of the team.

Most people would describe this as how they make decisions, albeit in a slightly more informal manner. However, the strength of this model lies in completing each step before moving on and closing the loop with the follow-up.

For example, within the diagnosis formulation step, it is essential not to grasp the first hypothesis so tightly that no other possibility is considered. The inner cycle of formulating a diagnosis and collecting data should be repeated to ensure you have considered multiple options before moving to the solution planning step. And solution planning should consider all the solutions, and evaluate their strengths and weaknesses, before advancing.

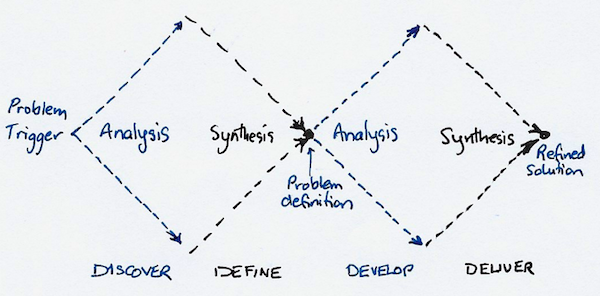

4. Design Thinking

Design Thinking may seem a strange process to apply to decision making because it is best known for solving product and service design problems. I find it particularly strong for checking you’re solving the right problem in the most effective manner. This makes it an excellent framework for making decisions when the root cause of a problem has been difficult to establish.

The following description talks about ‘problems’, but it is just as easily applied to ‘opportunities’.

The first half of the process focuses on determining the true nature of the problem. Don’t assume: look at the evidence. Use techniques such as ‘The Five Whys’ to create a proof for your problem definition.

Then develop ideas that might solve the problem. You might start with the question “How might we…?” Or “What is the riskiest assumption…?”

The deliver stage usually involves a series of tests to check if our proposed solutions work. The use of prototypes can mean initially accepting imperfectly formed answers but further iterations will achieve an optimised solution.

This method is a good way of approaching a decision you feel fits Jeff Bezos’ Type 1 door metaphor. You benefit from knowing the core question giving rise to the problem or opportunity, and you discover a proven path to your desired outcome. This can be critical to convincing senior stakeholders or engaging a large cross-functional team in the decision making process.

Summary

These are four methods that have worked for me in a variety of settings, but I’m keen to hear about other decision making models that have helped you.

The models I’ve used all make use of:

- Iteration, each approach has a closed loop structure, encouraging faster moving, self-correcting activities.

- Data collection and analysis helps avoid cognitive biases and unvalidated assumptions.

- Generating alternatives forces us to use comparative option-taking which improves the quality and consistency of decision making.

Always review your decisions with the people who have been involved or impacted. Post-match analysis will happen with you or without you. Formally, or informally, your managers, peers and staff will evaluate your decisions and it is in your interests to focus these conversations on the agreed mission objective. There are commonly multiple sets of expectations and the best way of ensuring alignment is to work to an agreed outcome from the outset. You can then use the desired outcome at each step of the process to focus the analysis and measure the final result.

Be careful when helping review other people’s decisions. Daniel Kahneman captures this beautifully in Thinking Fast and Slow, saying: “Because adherence to standard operating procedures is difficult to second-guess, decision makers who expect to have their decisions scrutinized with hindsight are driven to bureaucratic solutions — and to an extreme reluctance to take risks.”(emphasis mine) In other words, when judging the decisions of others, don’t be a Captain Hindsight.